Decarbonizing Transportation, at Scale

Commercial vehicles could go zero. What could possibly go wrong?

Last month, at Europe’s biennial shindig for the commercial vehicle industry IAA Transportation1, some of the world’s largest truck manufacturers presented their vision for some of the world’s largest trucks:

Daimler Trucks (which owns Mercedes-Benz, Freightliner, Thomas Built and other brands) unveiled battery-electric eActros2 LongHaul truck concept prototype. Traton Group’s MAN (Scania, MAN, Navistar, Volkswagen) presented the fully battery-electrified truck prototype eTruck, scheduled to arrive at customers in two years. Newcomer Nikola and partner IVECO started taking orders for the Nikola Tre BEV Heavy-Duty Truck (and showcase the FCEV prototype). You get the pattern.

This is a remarkable development. As recently as four years ago, at the last IAA Commercial Vehicles show (pre-pandemic), manufacturers hedged their bets by pursuing some variant of multi-pronged approach including “advanced” diesel technology, natural gas vehicles, battery-electric (including those with pantographs for overhead catenary cables), and fuel-cell electric vehicles. Especially heavy trucks were deemed all but unfit to be battery-electrified, both for reasons of weight and reach – especially in the long-haul segment.

The common refrain until very recently: Langsam, it’s too early to settle on one technology. Now it’s a near unanimous “Electrify!” love fest.

This seemingly3 monumental shift begs two questions:

What happened?

What could possibly go wrong?

To find answers to these questions, I did some research, and interviewed people smarter and more knowledgeable than me. I thank Kerstin Andreae and Dr. Jan Strobel of BDEW, the German Association of Energy and Water Industries, and Professor Dan Sterling, Founding Director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis.

1. What happened?

Two things happened. First, advancements in battery technology put paid to the batteries-are-not-for-trucks adage. Prices have come down, capacity has gone up, and BEVs are now the first choice globally for Zero Emission Vehicle technology4.

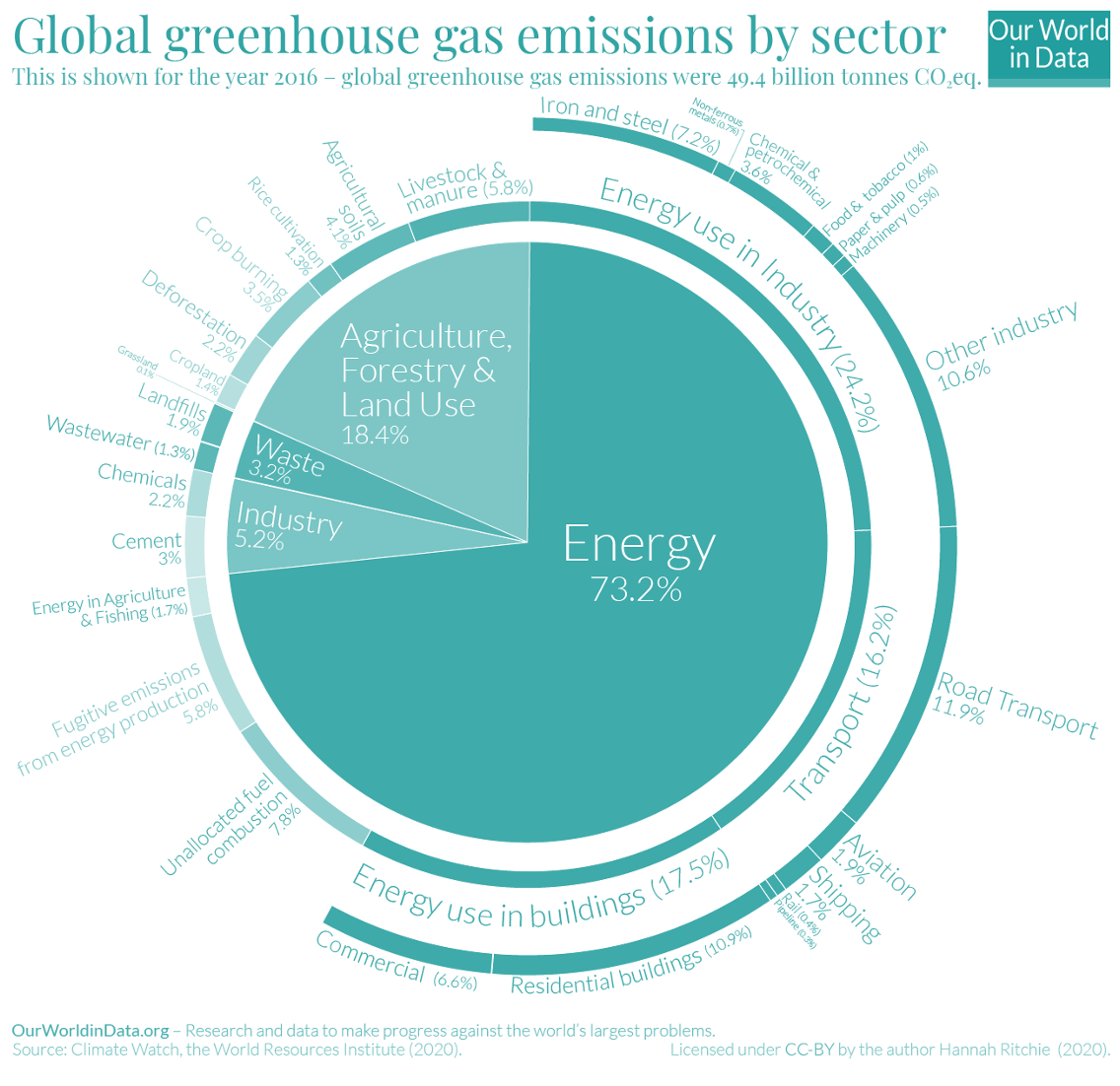

But this development, sans internalized environmental cost, did not happen by market forces. It’s not driven by the intrinsic needs of the transportation sector (which would entail increasing load factors, multi-modal efficiency etc), but by the all-encompassing climate crisis, which is to ¾ an energy sector problem5.

Electrification is neither mandated by the EU, nor the US6. But zero emission vehicles (ZEV)7 increasingly are: California requires new passenger cars and light trucks sold in the state to be zero-emission by 2035. (12+ states typically follow California’s regulatory lead, constituting about a third of the US market – usually enough to influence manufacturers’ sales strategy for the entire country.) The EU is poised to also mandate that by 2035, all new passenger cars and vans sold in the EU are zero-emission vehicles (ZEV)8.

It’s hard to overestimate the power of ZEV mandates: Requiring a manufacturer to produce a car without exhaust is a radically different regulatory approach to just limiting pollutants: it asks to create a new, not an improved or amended technology9.

As a regulatory tool, it’s relatively new to the EU, but an old hat in the US:

The California Air Resources Board CARB10 pioneered ZEV regulation in 1990. The ensuing struggle was later documented in the film Who Killed the Electric Car?

All current ZEV passenger vehicle models available to purchase or lease are BEVs. Given the tight deadline, it seems highly likely BEVs will constitute the vast majority of passenger vehicles sold after 2035.

ZEV Regulation fuels the transition to BEVs, leading to increased investment, advancement and intellectual property accrual in battery technology.

But passenger car regulation and battery development alone could not have predetermined the choice of zero emission technology for commercial vehicles. The world has a long history of treating these very different segments very differently: for decades, gasoline was for cars, and Diesel was for trucks, which also reflected in different sets of regulation.

The second thing happening: Commercial vehicle regulation followed passenger car regulation – and that was just the first step.

California’s current Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) Regulation of 2019 established a ZEV phase-in starting in 2024, broken down to different vehicle segments. For 2035 and beyond, the regulation mandates sales percentages of 55% (for classes 2b – 3), 75% (for classes 4 – 8), and 40% (for classes 7 – 8)11.

ATC all but guarantees that the entire range of medium-duty vehicle sales would be majority-ZEV by 2035, and thus accelerated the decision-making process in automotive headquarters. Following the precedence of cars, BEV tech for trucks is on the rise.

But CARB this year drove the point home by proposing an Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) Regulation. It includes a ZEV sales percentage requirement for all medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, beginning 2040: 100%. And even though ACF is about fleets, CARB makes it abundantly clear what “all” means: “This requirement impacts all fleets and individuals who purchase medium- and heavy-duty vehicles in California.”

Dan Sperling points out, that ACF would have minimal effect by itself. But it supercharges ATC.

And in the EU? Until this year, the EU did not have ZEV regulation, it remained content to tighten emission regulation for pollutants, and efficiency regulation, limiting GHG emissions. But as we have seen above, they introduced a – nominally tech-neutral – ZEV mandate for passenger cars in their Fit-for-55 package.

This year, a review of the existing CV regulation is on the books; it’s too early to say whether the EU will follow California’s ZEV lead, again. According to The International Council on Clean Transportation ICCT, it should – at least if it were to meet its climate goals. The proposed phase-out date for ICE trucks: 2040.

What happened? Regulation, that’s what happened. Between the technologically ambiguous IAA 2018 and the more ambitious IAA 2022, regulation in the transatlantic truck market went from limiting to outlawing pollutants and GHG emissions. Manufacturers look to electric propulsion to meet that mandate.

2. What could possibly go wrong?

Obviously, a lot. Supply, infrastructure, political and societal support, and plain economics all need to align for decarbonization of transportation to happen, at scale. Let’s look at the necessary conditions for success:

Adequate Energy Supply, Grid and Infrastructure

“Electrify everything + decarbonize the grid” is the prevailing mantra of energy transition experts across the globe. Yet “decarbonize the grid” means

generate more carbon-free electric energy,

upgrade the grid to handle more intermittent, and more decentralized, renewable power generation including storage, and additional demand from transportation including managing new peaks, and

build the infrastructure to deliver energy to the vehicles.

Putin's weaponization of energy supplies laid bare the failures of Germany's energy and russia policy of the last 15+ years: the upcoming winter might lead to blackouts and/or gas shortages12, while citizens and companies are being priced into bankruptcy.

natural gas*: +480%.

butter: +49%

prices in Germany compared to a year ago. *new contracts

This is a major crisis that not only calls for immediate and robust intervention to alleviate the worst, but also might very well have detrimental, long-term social and economic impacts. Both Germany’s industrial leadership and societal cohesion might be at stake.

Yet federal government and energy industry alike see this as a call for accelerated transition to sustainable energy (in face of a very vocal, and very angry, opposition that demands the opposite).

I asked BDEW which kind of upgrades they deemed necessary to supply, grid, and infrastructure as both passenger and commercial vehicles were transitioning to electric propulsion. After all, these had been bottlenecks to electrification for years.

The answer of Dr. Strobel was testament to the momentous shift the current crisis has brought about: “The transformation in Germany is ongoing and not driven by the future electrification of the transportation sector but ahead of it.”

Whatever transformational aches & pains the transportation sector might experience: they pale in face of the acute energy crisis. The supply of renewable energy will be ramped up regardless, as will the production of green hydrogen.

Similar developments can be seen across the Atlantic: The Inflation Reduction Act includes the most substantial investments in and incentives for renewables in US history. The impact could be even greater than already anticipated: according to The Atlantic, reporting on an assessment by Credit Suisse, “the climate economy Is about to explode.”

California just decided to let its nuclear power plant run a little longer, but only to support its path to “electrify everything + decarbonize the grid”. California’s grid already handled a historically extreme heat wave exceptionally well, while being well on track to become 100% renewable by 2045.13

Prediction: The energy transition is happening, and will continue to happen at an accelerated pace. Chances are: these developments will include supply, grid and infrastructure for transportation.

Continued Political and Societal Support

Of course, the above phrase and will continue to happen at an accelerated pace can seem premature. The current and possibly upcoming mandates set targets at a massive scale14. A necessary condition for any progress is for these mandates to stand. Any regulation, in order to be effective, must be

designed in a way that ascertains the desired outcome once implemented

enforced (and possibly improved upon) once signed into law,

survive changes in government, and

adopted by even more states and countries15. (Repeat.)

The current laws and regulations, and those in process, are all more ambitious, far-reaching, and with more teeth, then what we’ve seen in the last two decades. We see this both on the state and national level in the US, and in the country and European level east of the Atlantic.

California will vote in a month’s time. It will most certainly remain majority-Democratic, with Gavin Newsom – even more ambitious and decisive after the a recall – remaining at the helm. The state seems to have no appetite to relinquish its climate policy leadership.

The US midterm elections might bring the end to Democrat’s supermajority on the national level, with the House turning Republican, and the Senate a toss-up. But the president remains Biden for the next two years, and IRA is already the law of the land.

The EU’s standing, regulatory ambition and policy power has de facto increased after Brexit, and during the pandemic. Fit-for-55 will most likely pass, and will be the most muscular and far-reaching climate action by the union ever. The EU’s also more comfortable today to enforce EU regulation in case she finds member states’ actions lacking.

In Germany’s 3-party government, the ambitious and competent Greens16 are in charge of economic, climate and environmental policy. But they operate under the directive authority of the more cautious chancellor of the Social Democrats and have to find common ground with the center-right Liberal finance minister. Despite some kerfuffles, there are no signs of the coalition breaking up or becoming ineffective. Since it has another three years to go, the "Energiewende" should continue.

This comes with a caveat: Russia’s war on Ukraine, and by proxy the West, might shift public opinion, or political necessities, into unforeseen territories – as is clearly Putin’s intend. So far, he has achieved the opposite, but the most recent survey has painted a bleaker picture (it didn’t specifically ask about support for Germany’s energy policy).

Prediction: Sufficient societal and political support should remain for decarbonization, including that of transportation.

Economics and Technology

Short of regulatory roll-back, there’s the possibility that a technology other than electric propulsion would emerge that would allow us to reach the mandate’s goal more economically. Proponents of eFuels argue that creating carbon-neutral fuels for ICE vehicles could achieve that – and faster, since these fuels might also be compatible with existing fleets (which otherwise would take 20+ years to be phased out).

Yet a viable path to have eFuels ready at scale and at the time needed – disregarding for a moment that they are highly inefficient and not pollutant-neutral – is not in the offing. The necessary precursor – green hydrogen – is already in short supply, currently expensive to produce, and more effective if used directly in FCEVs. FCEV are already part of some manufacturer’s plan for the most demanding versions of heavy-duty trucks.

eFuels are the only semi-viable option for internal combustion engines to survive the energy transition17, and to stymie electrification. The status quo – technical or otherwise – has tremendous staying and political power, especially if the new doesn't significantly improve direct use experience or results. A lot can change in just a few years, and manufacturers’ transition to electrification is – bar for newcomers like Nikola – not locked-in. But as of now, IAA seems to point one way.

If electrification will prevail there are a few variants worth noting:

– Electric Road System Vehicles (ERSV)

OECD/ITF posits that ERSVs “have the potential to be the most cost-competitive technologies in Europe” to decarbonize road transport18. Efficiency is an important business driver in the transportation sector, but cost-competitiveness with Diesel ICEVs might not matter once they're effectively outlawed.

As of now, this technology gets persistent, yet limited traction – and mostly in Europe: Daimler declared, as a globally operating company, it would not pursue this technology further. Scania will. It might be too early to call it off entirely.

– Battery Swapping

Battery swapping, as originally championed by Shai Agassi’s Better Place, has found its reincarnation in Nio (as a proprietary service for Nio passenger cars), and Ample19 (a modular, manufacturer-agnostic), which also focuses on fleets.

There are some valid arguments to be made for swapping: Charging batteries independent of vehicle operations might be easier on the grid if charging large fleets. ELMS, a clean commercial vehicle startup, cooperates with Ample for their vans. As an aftermarket solution, a modular swapping solution allows for mixed fleets, which many are (Uber is a partner).

– Bundles

Nikola adapted Tesla’s business model to commercial vehicles: Nikola provides both the vehicles as well as the infrastructure for BEV and FCEV (and also hydrogen generation). As many fleet operators are used to have their own energy (gasoline/petrol and diesel) supply at their premises, this seems to be a sensible approach – and even more monetizable than Tesla’s charging network.

Prediction: “Electrify everything” via BEV, and for some cases via FCEV, will prevail. Energy and its delivery might become a service beyond the charging station.

So, all is good? We’ll decarbonize our grid, move everything to become electric, and make a killing with new business models because of it? Of course it's not that simple. None of this will happen unless unless we marshal the resources necessary, unless we push forward relentlessly on an urgent time schedule, unless we remain steadfast in face of obstacles, unless we choose a better future over the complacency of today.

We have the once-in-a-generation chance to create all the necessary conditions in a way that we weren’t available to us before. Decarbonizing transportation, at scale, is within reach like it hasn’t been in decades. It’s a chance we shall not waste.

This newsletter is called rising to remind us, that we always have the option to rise to the challenge, to seize the opportunities, and to create the future we want to live in. That spirit, that drive is the sufficient condition of success. There’s also nothing wrong with a shot of fast-forward optimism, n’est-ce pas?

Thanks for reading, and your patience to stick around until the end. Please share your thoughts. Subscribe if reading too-long newsletters once in a while is your thing.

Disclosure: Your author was in charge of marketing of IAA (both cars and commercial vehicles) from 2007 to 2015, and for IAA’s business transformation platform New Mobility World + IAA Conference (including Logistics edition) from 2016 to 2019.

Disclosure: Your author was in charge of the marketing agency team for Mercedes-Benz commercial vehicles from 1997 to 2003, including the launch of the Actros line.

It’s still largely a shift in announcements, not in sales. Virtually all trucks sold today run on Diesel. Vans, delivery trucks, city buses already see some degree of electrification.

Why that is, and why that’s a good thing, I discussed earlier. And even though the requirements of commercial vehicles differ greatly from those of passenger cars, the more investment, advancement and intellectual property is accrued in one segment, the easier it generally is to spill into the other.

The US and EU car and light truck/SUV markets are roughly comparable in size. The car segmentation works a bit differently in either. SUV and pickups, albeit used mostly for passenger transport, fall into the light truck segment.

ZEV: zero emission vehicle (emitting neither CO2, nor regulated exhaust fumes like N2O). This term is technology-neutral. A quick refresher on the other abbreviations:

BEV = battery-electric vehicle (charged with electric current). FCEV = fuel-cell electric vehicle (fueled with hydrogen). ICEV = internal combustion vehicle (fueled with gasoline/petrol or Diesel, natural gas or even hydrogen). CV: commercial vehicle

Commission, Council and Parliament have all voted in favor to mandate ZEVs. Trilogue negotiations to reconcile the three documents are supposed to start at about this time: after the summer break of 2022.

From a commercial vehicles perspective, all passenger cars are alike. The use cases, and requirements for CVs, are as diverse as the entire economy itself: commercial vehicles transport and deliver goods, are the mobile, and individually outfitted, work stations of bazillion different professions, they move dirt off-road in construction and people across cities. They truly are the backbone of any advanced economy based on the division of labor.

CARB is to car emission regulation what Stanford University is to Silicon Valley: the latter would not exist without the other. CARB was instrumental to phase out lead from gasoline, in mandating catalytic converters, and in exposing Dieselgate.

roughly, these groups can be categorized as a) the commercial tail-end of light trucks, eg larger pickups, b) medium-duty, eg delivery vans or school buses, c) heavy-duty, eg long-haul trucks

For context: Blackouts, just like unsafe drinking water, are virtually unheard of in Germany. Reports of those from across the Atlantic are seen as part and parcel of US exceptionalism, just like gun violence.

In an echo of the current debate in Germany, some see the “we barely made it”-moment of the heat wave as a reason to slow down, or call into question entirely, the transition to renewables.

Not suggesting ICE cars should be replaced 1:1 with ZEV – on the contrary. But even if alternatives like public transport were to take a substantially larger modal share before the target dates – a big IF, given the current state of transit systems, the amount of deferred maintenance, and how long public work projects nowadays take – it would still be a momentous task.

Nobody knows this better than California, which takes a very active role to lead and disseminate decarbonization regulation around the globe. On page no. 10 (and page 27 of the PDF) of Proposed ACF Regulation you’ll find a summary of those efforts.

Your author is clearly biased: he’s a party member. But Green cabinet members, for now, enjoy higher approval ratings than those of their peers – or opposition leaders.

You can also use hydrogen as an ICE fuel, yet you’ll need a modified engine: it’s not a drop-in solution like eFuels. Just like eFuels, it will still emit N2O. The efficiency of an H2-fueled ICE is similar to an engine running on diesel or gasoline/petrol. I discount the chance of wide-scale adoption of ICE+H2 as it’s somewhat of a meh-option: pros and cons seem to balance each other out. This doesn’t mean that eFuels are dead: they are most likely needed for aviation, the maritime sector and some edge use cases.

Your author admits that he has an “odd duck” feeling about trucks with pantographs: you’ll obviously will have to use dedicated routes to utilize the electric road system, so why not use rail instead if you’re to give up the flexibility of the road system? But I admit to not having looked into all the potential use cases.