Decarbonization: Not a market.

Policies to Future-Proof Germany's Automotive Industry until 2030, Part 1 of 3

In about 2.5 months, we’ll elect a new government in Germany. There is a chance for the Green party to be part of the future government. Against this backdrop, the Heinrich Boell Foundation recently asked me: “What are the policies to future-proof Germany’s automotive industry until 2030?”1 We agreed to define “future-proof” as

competitive: technologically leading and globally successful,

sustainable2 in production and products,

providing good employment and high value added in Germany.

I clustered my answers into three categories: decarbonization, digitization and progress, each with three distinct recommendations – too much for one newsletter alone. If you don’t want to miss the next ones in this mini-series, and haven’t subscribed yet:

The future according to Germany, eleven years ago

Germany was late to join the decarbonization game3: It was only in 2010 that the German government formed the advisory council National Platform for Electric Mobility NPE4, along the joint ministerial agency GGEMO. It was the most comprehensive measure yet in a country that, merely 2.5 years prior, had acknowledged that “electric vehicle drives offer the greatest potential in the medium and long term to reduction of transport-related CO2 emissions”.5

The stated goal for 2020: Germany should become both the global lead market and lead supplier of electric mobility, with 30,000 additional jobs created and 1 million EVs on German roads.

Only the 1-million-bit of that goal came to fruition6, albeit barely, and with a minor detour via the biggest industry scandal in post-war Germany.7 It was an arbitrary goal, with no science involved. It soon morphed from slogan into a benchmark to identify a self-sustaining market, defined by relying less on incentives and regulation.

1 million EVs, but no “Markthochlauf”

Once 1 million benchmark was reached, people’s collective preference was supposed to switch to EVs, ditching their ICEs en masse.

The NPE even introduced a new word for this: “Markthochlauf”, or market ramp-up. It has remained a cornerstone of the political debate since.

But self-sustaining the German EV market is not. Instead, incentive programs continue to be prolonged and expanded, and regulations to be tightened. Yet the believe in a self-sustaining EV market is alive and well in Germany, and still undergirds debate, policy, and regulation: NPEs successor organization National Platform for Future Mobility NPM argues for the continued subsidies for Plug-in Hybrid EVs, or PHEVs, because they would enable the transition to electric mobility for buyers8. PHEVs are disproportionately subsidized in Germany, leading to a higher share in total EV shares (50% against 25% worldwide).

So, if 1 million EVs didn’t get us there, when will demand for EVs become self-sustainable?

EVs are becoming fashionable worldwide

Globally, electric propulsion, combined with a battery for energy storage, is the leading alternative to internal combustion engines (ICEs) running on fossil fuels. All other alternatives – e.g. fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) running on Hydrogen or ICEs running on alternative fuels (natural gas, plant-based, fuels derived from hydrogen) – lag far behind BEVs.

Today, electric vehicles (EVs, including PHEVs) make up about 3% of all new vehicles sold annually worldwide, with a total of 12 countries reaching a minimum of 1%. EVs have become fashionable, yet they’re still mostly high fashion: pricey, somewhat experimental, exclusive.

Only in Norway, EVs have moved from high street to main street. The difference: the country started to promote the sale of EVs 30 years ago – a head start on Germany and most other countries of 20 years –, through a multitude of measures9. Today, with 56% market share, the country continues to regulate and incentivise the transition to electric propulsion.

Regulations and promotions are not mere accelerants; they are the necessary drivers of transition: In every single country with at least 1% market share, a combination of incentives and punitive measures is in place. Put differently:

Nowhere on this planet10 are EVs sold in any significant numbers without robust measures in place – regardless of how wealthy or environmentally minded or novelty-driven the population might be.

“Markthochlauf” is a dangerous myth.

Norway puts it succinctly: “The speed of the transition is closely related to policy instruments and a wide range of incentives.“ This describes the opposite of a functioning, self-sustaining market.11 Yet “Markthochlauf” continues to be a cornerstone of German policy and debate. Why?

Favoring market forces over forced markets, and keeping technical options open, are laudable notions – in fact, they are the cornerstones of market economies. Alas, pretending to operate in a functioning market is not creating one. (All economies, market or otherwise, have failed to account for ecological externalities.)

“Markthochlauf” implies a gentle, transitory nudge, rendering suggested government interventions more palatable to constituents. But it invites doing too little, too gently, while still binding considerable resources: Significant amounts of capital and brainpower12 were poured into so-called four-year showcase projects (“Schaufensterprojekte”13), resulting in 22 recommendations for action, all of them groundbreaking (and just as inconsequential) as number 18: “Public transport should increasingly use electric buses in the inner cities”.

“Markthochlauf” delays a transition that gets only more disruptive down the road. It kept industrial (and Germany’s collective) focus on ICE profits, and jobs. That alone could not explain the criminal mindset to commit the Diesel scandal, but defeat devices would have served less of a purpose. Significant legal, economical and technical resources continue to be wound up in the aftermath of this fraud – from lawsuits to retrofits14.

It’s convenient if you want to keep questioning the rationality of electrification. There’s a valid argument to be made that BEV might not fit all use cases in every part of the world, but it’s been used to discredit the push for electrification wholesale – sometimes explicitly citing the non-market, political directive nature of that push. In that narrative, “Markthochlauf” failed, and if markets don’t want BEVs, then they’re not the right answer after all.

Pretending comes with real cost – to the environment, the taxpayer, and – in the long run – to the industry. It misallocates resources, neglects responsibilities, and delays progress. The next German government needs to do stop pretending that decarbonization is a market.

What to do? (What government does best.)

For the next German government to succeed in facilitating a future-proof German automotive industry, they need to stop pretending: A future EV self-sustained market will arise only when transition is completed, and not one car earlier15.

This will need sustained, robust, flexible use of policy instruments and incentives on every level of government, closely coordinated with the EU, US and other important markets, along clear goals, and a sensible path to success.

Waiting for “Markthochlauf” results in a lack of goal-oriented, forward thinking (to avoid the toxic word planning). One of the most dramatic, and entirely preventable16 such failures of German (and EU) governments has been infrastructure:

For a healthy, future-proof industry, nothing is as important as demand. Without demand, there are no sales.

Two studies - one from Cardiff University, one from Chang'an University - have compared the demand effectiveness of different instruments internationally. Both independently conclude that infrastructure drives demand: "If the government increases the density of charging points by 1%, this will increase e-vehicle use by 0.9%." The advantage of infrastructure investment over other measures: it stays, even if other benefits expire.

Infrastructure is a basic public service, and as such government task. Government doesn’t need to directly construct or operate, but laissez-faire is not an option. (The recurring stance that it’s the energy companies’ or car manufacturers’ duty to provide infrastructure, borders on political malpractice.17)

Governments are in a unique position when it comes to infrastructure – and the economic powers of infrastructures (often natural monopolies) can hardly be overstated. The state must ensure that it is available in sufficient quantities and that access is regionally and socially equal – especially since EV adoption closely tracks income levels.

A nationwide, high-performance charging infrastructure is the single most effective measure at a governments’ disposal to boost demand – furthering decarbonization and the path to a future-proof industry.

The German and European status quo is a hinderance to demand, and therefore a direct hinderance to a future-proof automotive industry18. ACEA and TE don’t always agree, but on the need for 3 million charging points by 2030, they do.

The second best thing

If the future government had only one shot, infrastructure it should be. The battery-electric drive is the first choice in terms of climate policy. But, as the world map at the beginning has shown, BEVs are not a one-fits-all solution. What to do with

the need for smaller and cheaper cars for people living in multi-family-homes - e.g. the home health caregiver?

heavy and/or long-distance transportation - e.g. long-distance trucks, construction trucks?

spontaneous and fast - e.g. police?

beyond northwest Europe, ROW and existing fleets?

A future government cannot shy away from scenarios that aren’t conductive to BEV applications. Especially since the very question of which applications actually fall into this category, if any, is hotly disputed, and that’s putting it mildly. The follow-up question of which complementary fuel/technology combinations – e.g. ICE+eFuels, ICE+CGH2, FCEV+LH219 – should be advanced, isn’t settled either.

This newsletter is too long already; the entire debate, including energy sources, infrastructure, geopolitics is too complex to squeeze into another paragraph – and too important.

But in terms of climate policy, but also industrial policy, it is necessary to reach a path decision in Europe in the next two years. This is because, as with the regulation and promotion of and infrastructure for battery-electric drives, this second best technology would also require significant support from the state.

I applaud and thank you for reading this far. I promise, the next part – digitisation – will be shorter. Let me know what you think – and share if you like.

They are based on a keynote lecture I had the honor of holding at Heinrich Boell Foundation’s conference on Construction Site: Future-proof industry.

“Sustainable” has a lot to lift here, touching on at least five of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, with decarbonization at the forefront of a roster of more specific goals, e.g. equitable mobility in liveable cities.

California was first to mandate zero-emissions vehicles (ZEV) in 1990 and to adopt low-carbon fuel standards in 2009 worldwide. It also has been a trailblazer to reduce “classical” air pollutants such as NOx, SOx and PM. What California regulates, sooner or later the US, and subsequently the world, adopts.

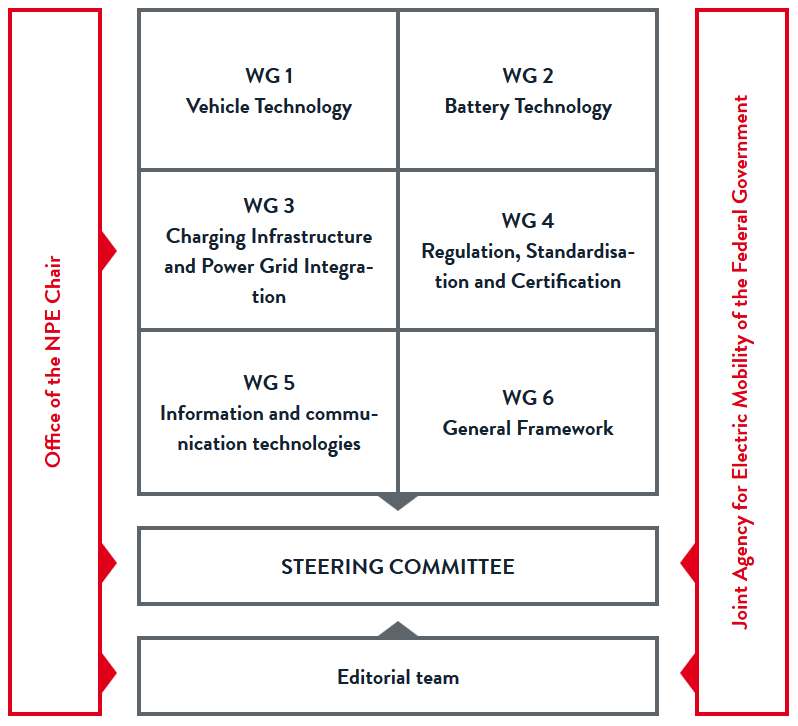

The steering committee consisted of top representatives of industry, politics, science, associations and unions, with many more people engaged directly and indirectly in six working groups. The joint agency was formed between four ministries.

At the Meseberg-Klausur in 2007, the federal cabinet identified 29 measures to reach the internationally agreed climate goals for 2020. Measure 26 pertained to electric mobility.

The NPE could not celebrate reaching the 1 m vehicles milestone in 2020, nor ever had to explain how Germany missed all other targets: neither worlds’ leading supplier nor market of EV, and definitely not a self-sustaining market: it was dissolved two years prior.

Without the Diesel fraud scandal, Volkswagen, Europe’s largest manufacturer, would probably have not performed quite the U-turn towards electric mobility the way it did.

See NPM PHEV report from October 2020, page 4. Subsidies for PHEVs in relation to BEV subsidies, are particularly high in Germany compared to other countries. So is the share of PHEVs in relation to BEVs. The actual usage of the electric drive train in PHEVs in Germany is low, rendering the actual decarbonization benefit negligible.

Norway’s EV measures since 1990:

1. No purchase/import taxes (1990-)

2. Exemption from 25% VAT on purchase (2001-)

3. No annual road tax (1996-)

4. No charges on toll roads or ferries (1997- 2017)

5. Maximum 50% of the total amount on ferry fares for electric vehicles (2018-)

6. Maximum 50% of the total amount on toll roads (2019-)

7. Free municipal parking (1999- 2017)

8. Parking fee for EVs was introduced locally with an upper limit of a maximum 50% of the full price (2018-)

9. Access to bus lanes (2005-)

10. New rules allow local authorities to limit the access to only include EVs that carry one or more passengers (2016)

11. 50 % reduced company car tax (2000-2018)

12. Company car tax reduction reduced to 40% (2018-)

13. Exemption from 25% VAT on leasing (2015-)

14. Fiscal compensation for the scrapping of fossil vans when converting to a zero-emission van (2018-)

15. Allowing holders of driver licence class B to drive electric vans class C1 (light lorries) up to 4250 kg (2019-)

Mars, on the other hand, sports a 100% EV share, as discussed in March.

A functioning market would meet two conditions:

The necessary condition: For markets to work price points need to internalize external costs, e.g. reflect the ecological reality.

The sufficient condition: the transition would need to be easier and more attractive than to switch from an iPhone to an Android, e.g. overcome lock-in effects.

Both conditions are neither reality, nor can be achieved within the necessary timeframe. At this point, for carbon pricing in transport to be effective, it would also be prohibitive, crashing instead of transforming the market, and probably detrimental to the most vulnerable citizens.

500 partners from business, science and the public sector were involved in 145 projects in four showcase regions, spending 400 M€, and uncounted person hours.

Literally “display window projects” – almost comically close to the phrase “window dressing”

The US was quicker to make the Diesel fraud a thing of the past: cars were taken off the street, customers fully reimbursed, culprits arrested and tried, fines paid. In Germany, retrofitting enters its fifth year, access CO2 and pollutants are still emitted, legal battles are still in full swing.

From an urban and mobility policy perspective, I do not advocate to swap ICE vehicles for EVs, or to keep public transport at the sometimes underfunded, under-innovated, under-integrated, under-comfortable and under-equitable level of service it operates at today, or to keep cities as car-centric as they are today. This article is about industrial policy –whatever the future use cases are, we’ll keep producing, using, exporting cars, vans, trucks and buses (and everything in between and beyond) – and how to facilitate a future-proof automotive industry.

In 2012, the Heinrich Boell Foundation and the German Association of the Automotive Industry VDA jointly conducted Auto 3.0 – The Future of the Automotive Industry, a series of talks and conferences. (I had the honor to be in charge on VDA’s side.) Even back then we talked about infrastructure being vital, and for government’s need to take the lead.

Tesla clearly saw the role infrastructure (and easy access!) plays in demand, but OEM-dedicated charging stations aren’t conductive to a viable business model or network.

and, of course, decarbonization

ICE+eFuels, refers to using synthetic fuels in slightly modified ICE vehicles; ICE+CGH2 uses compressed hydrogen; FCEV+LH2 uses liquified hydrogen in a fuel cell powering an electric motor.